There are certain assumptions that are applied to anyone labelled a “conspiracy theorist”—and all of them are fallacies. Indeed, the term “conspiracy theory” is nothing more than a propaganda construct designed to silence debate and censor opinion on a range of subjects. Most particularly, it is used as a pejorative to marginalise and discredit whoever challenges the pronouncements and edicts of the State and of the Establishment—that is, the public and private entities that control the State and that profit from the State.

Those of us who have legitimate criticisms of government and its institutions and representatives, who are therefore labelled “conspiracy theorists,” face a dilemma. We can embrace the term and attempt to redefine it or we can reject it outright. Either way, it is evident that the people who weaponise the “conspiracy theory” label will continue to use it as long as it serves their propaganda purposes.

One of the most insidious aspects of the “conspiracy theory” fabrication is that the falsehoods associated with the term have been successfully seeded into the public’s consciousness. Often, propagandists need do no more than slap this label on the targeted opinion and the audience will immediately dismiss that viewpoint as a “lunatic conspiracy theory.” Sadly, this knee-jerk reaction is usually made absent any consideration or even familiarity with the evidence presented by that so-called “lunatic conspiracy theorist.”

This was the reason why “conspiracy theorist” label was created. The State and its propagandists do not want the public to even be aware of inconvenient evidence, let alone to examine it. The challenging evidence is buried under the “wild conspiracy theory” label, thereby signalling to the unsuspecting public that they should automatically reject all of the offered facts and evidence.

There are a number of components that collectively form the conspiracy theory canard. Let’s break them down.

First, we have a group of people who supposedly can be identified as conspiracy theorists. Second, we have the allegation that all conspiracy theorists share an underlying psychological weakness. Third, conspiracy theory is said to threaten democracy by undermining “trust” in democratic institutions. Fourth, conspiracy theorists are purportedly prone to extremism and potential radicalisation. Fifth, conspiracy theory is accused of not being evidence-based.

According to the legacy media, there’s a link between so-called “conspiracy theory” and the “far right” and “white supremacists.” Guardian columnist George Monbiot, for example, wrote that:

[. . .] conspiracism is fascism’s fuel. Almost all successful conspiracy theories originate with or land with the far right.

Apparently, this is a common belief held by people who imagine that “conspiracy theory” exists in the form they have been told it exists. It is also a bold claim from an alleged journalist. There is no evidence to support Monbiot’s assertion.

Numerous studies have tried to identify the common traits of conspiracy theorists. These studies tend to initially identify their subject cohort simply through opinion surveys. If, for example, someone doesn’t accept the official accounts of 9/11 or the JFK assassination, the researchers label them “conspiracy theorists.”

Probably the largest demographic study of these alleged “conspiracy theorists” was undertaken by political scientists Joseph Uscinski and Joseph Parent for their 2014 book American Conspiracy Theories. They found that “conspiracy theorists” could not be categorised demographically.

Ethnicity, gender, educational attainment, employment and economic status and even political beliefs were not indicative. The only firm trait they could isolate was that conspiracy theorists, so-called, tended to be slightly older than the population average—suggesting, perhaps, that scepticism of State narratives increases with life experiences.

Professor Chris French made this observation, as reported by the BBC in 2019:

When you actually look at the demographic data, belief in conspiracies cuts across social class, it cuts across gender and it cuts across age. Equally, whether you’re on the left or the right, you’re just as likely to see plots against you.

This is not to deny that a minority of conspiracy theories are promoted by people on the far right of the political spectrum. Nor that some on the far left don’t advocate other similar theories. A few “conspiracy theories” can be considered “racist” and/or “antisemitic.” But there is no evidence to support the allegation that “conspiracy theorists,” when compared to the general population, are any more or less likely to hold extreme political beliefs or promote extremist narratives.

George Monbiot is certainly not alone in his views, but his published opinion—namely, that conspiracy theories “originate with or land with the far right”—is complete nonsense. So let’s discard his claim right now as ignorant claptrap.

Monbiot’s allusion to “conspiracism” relates to the alleged psychological problems that supposedly lead people to become “conspiracy theorists.” The “conspiracism” theory is a product of the worst kind of junk science. It is primarily based upon the notoriously flaky discipline of experimental psychology.

One of the seminal papers informing the theory of “conspiracism” is Dead and Alive: Beliefs in Contradictory Conspiracy Theories (Wood, Douglas & Sutton, 2012). The researchers asked their “conspiracy theorist” subjects to rate the plausibility of various alleged conspiracy theories. They used a Likert-scale, where 1 is strongly disagree, 4 is neutral, and 7 is strongly agree. Some of the “theories” the subjects were asked to consider were contradictory.

For example, they asked the subjects to rate the plausibility of the notions that Princess Diana was murdered and that she faked her own death. Using this methodology, the researchers concluded:

While it has been known for some time that belief in one conspiracy theory appears to be associated with belief in others, only now do we know that this can even apply to conspiracy theories that are mutually contradictory.

But the researchers did not ask their subjects to exclude mutually contradictory theories—only to rate the plausibility of each individually. Thus, there was nothing in their reported findings to support the conclusion they unscientifically reached.

Subsequent research has highlighted how ludicrous their falsely named “scientific conclusion” was. Yet, despite being roundly disproved, the erroneous assertion that conspiracy theorists believe contradictory theories simultaneously is repeated ad nauseam by the legacy media, politicians and academics alike. It forms just one of the groundless truisms spouted by those who spread the “conspiracism” myth.

One of the most influential scholars—if not the most influential—in the field of conspiracy research is political scientist Joseph Uscinski. Like many other of his peers, he has tried to differentiate between evidence-based knowledge of real or “concrete” conspiracies, such as Iran-Contra or Watergate, and what scientific researchers allege to be the psychologically flawed and evidence-free views held by so-called “conspiracists.”

Uscinski cites the work of Professor Neil Levy as definitive. In Radically Socialized Knowledge and Conspiracy Theories, Levy stated:

The typical explanation of an event or process which attracts the label “conspiracy theory” is an explanation that conflicts with the account advanced by the relevant epistemic authorities. [. . .] A conspiracy theory that conflicts with the official story, where the official story is the explanation offered by the (relevant) epistemic authorities, is prima facie unwarranted. [. . .] It is because the relevant epistemic authorities — the distributed network of knowledge claim gatherers and testers that includes engineers and politics professors, security experts and journalists — have no doubts over the validity of the explanation that we accept it.

Simply put, the scientific definition of “conspiracy theory” is an opinion that conflicts with the official narrative as reported by the “epistemic authorities.” If you question what you are told by the State or by its “official” representatives or by the legacy media, you are a “conspiracy theorist” and, therefore, according to “the Science™,” mentally deranged.

All related “scientific research” on conspiracism and claimed conspiracy theory starts from the assumption that to question the State, the Establishment or the designated “epistemic authorities” is delusional. As hard as this fact may be for many to accept, the effective working definition of “conspiracy theory” in the scientific literature is “an opinion that questions power.”

Clearly, this definition is political, not scientific. The supposed underlying psychology of “conspiracism,” which allegedly induces people to engage in “conspiratorial thinking,” is an assumption stemming from the academic’s political bias in favour of the State and its institutions. It has absolutely no scientific validity.

In his 1949 essay Citizenship and Social Class, sociologist T. H. Marshall examined and defined democratic ideals. He described them as a functioning system of rights. These rights include the right to freedom of thought and expression, including speech, peaceful protest, freedom of religion and belief, equality of justice, equal opportunity under the law, and so on.

Most of us who live in what we call representative democracies are familiar with these concepts. “Rights” and “freedoms” are often touted by our political leaders, academia and the legacy media as the cornerstones of our polity and culture. The entire purpose of representative democracy, it is alleged, is to empower “we the people” to hold decision-makers to account. “Questioning power” is a foundational democratic ideal.

If we accept the working scientific definition of “conspiracy theory,” then its inherent questioning of power and overt challenge to authority embodies perhaps the most important democratic principle of all and forms the bedrock of representative democracy. It is not unreasonable to aver that representative democracy cannot possibly exist without “conspiracy theory”—again, as it is defined in the scientific literature. As we can see, the claim that “conspiracy theory” threatens democratic institutions is without merit.

Representative democracy is not founded on public trust in the State, in its agents or in its representatives. On the contrary, representative democracy is built upon the right of the people to question the State, its agents and its representatives.

Autocracies and dictatorships demand public “trust.” Democracies do not. In a representative democracy, “trust” must first be earned and, through their actions, State institutions must constantly maintain whatever trust the public originally chose to invest in them. Wherever and whenever that “trust” is no longer warranted, the people who live in a democracy are free to question, and ultimately dissolve, State institutions they don’t trust.

Trust is not a democratic principle. Questioning power is.

Consider that, according to State institutions like the United Nations (UN),

Conspiracy theories cause real harm to people, to their health, and also to their physical safety. They amplify and legitimize misconceptions [. . .] and reinforce stereotypes which can fuel violence and violent extremist ideologies.

This is a wholly misleading statement. It is disinformation.

The most violent act imaginable, and the most extreme ideology of all, is war and the all-out commitment to it. Full-scale war is possible only when a State declares it. International war is solely within the purview of one entity: the State. Wars are frequently justified by the State using lies and deception. Furthermore, the ideology of war is unwaveringly promoted by the legacy media on behalf of the State.

To be clear: the UN alleges that when ordinary men and women from across all sectors of society—representing all races, economic classes and political views—exercise their democratic right to question power, they are expressing opinions that “fuel violence and violent extremist ideologies.”

For such an extraordinary, apparently anti-democratic allegation to be considered even remotely plausible, it must be based upon irreproachable evidence. Yet, as we shall see, the UN’s claim is not based on any evidence at all.

In 2016, UN Special Rapporteur Ben Emmerson issued a report to the UN advising its member states on potential policies to counter extremism and terrorism. In his report, Emmerson noted the lack of a clear, agreed-upon definition of “extremism.” He reported that different UN member states defined “extremism” based upon their own political objectives and national interests. There was no single, cogent explanation of the “radicalisation” process. As he put it:

[M]any programmes directed at radicalisation [are] based on a simplistic understanding of the process as a fixed trajectory to violent extremism with identifiable markers along the way. [. . .] There is no authoritative statistical data on the pathways towards individual radicalisation.

A year later, in 2017, the US National Academy of Sciences (NAS) delivered its report, “Countering Domestic Extremism.” The NAS suggested that domestic “violence and violent extremist ideologies” were the result of a complex interplay between a wide gamut of sociopolitical and economic factors, individual characteristics and life experiences.

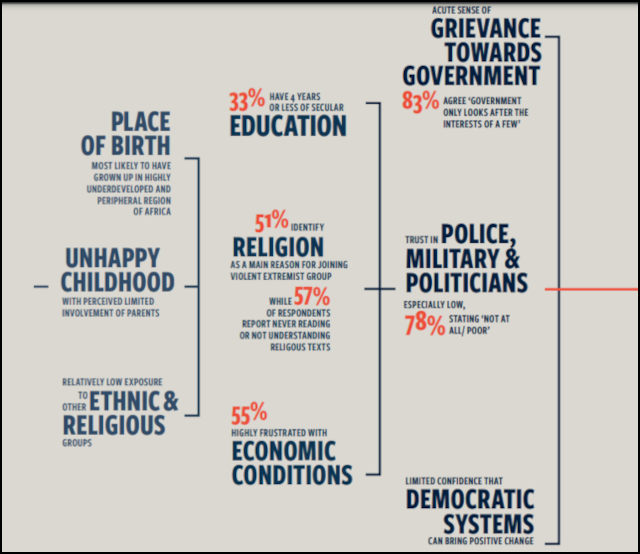

The following year, in July 2018, the NAS view was reinforced by a team of researchers from Deakin University in a peer-reviewed article, “The 3 P’s of Radicalisation.” The Deakin scholars collated and reviewed all the available literature they could find on the process of radicalisation that potentially leads to violent extremism. They identified three main drivers: push, pull, and personal factors.

Push factors are the structural factors that propel people towards resentment, such as State repression, relative deprivation, poverty, and injustice. Pull factors are factors that make extremism seem attractive, like ideology, group identity and belonging, group incentives, and so on. Personal factors are individual character traits that make a person more or less susceptible to push or pull. These include psychological disorders, personality traits, traumatic life experiences, and so on.

Presently, the UN maintains that its report, Journey To Extremism in Africa, is “the most extensive study yet on what drives people to violent extremism.” In keeping with all previous research, the Africa report concluded that radicalisation occurs through an intricate combination of influences and life experiences.

Specifically, the report noted:

We know the drivers and enablers of violent extremism are multiple, complex and context specific, while having religious, ideological, political, economic and historical dimensions. They defy easy analysis, and understanding of the phenomenon remains incomplete.

In its report called “Prevention of Violent Extremism“—published in June 2023—the UN noted that “deaths from terrorist activity have fallen considerably worldwide in recent years.” Yet, in its promotional literature for the same report, the UN claimed that the “rise of violent extremism profoundly threatens human security.”

How can the UN have it both ways? How can it be that a “rise of violent extremism” correlates with a considerable reduction in terrorist activity and associated deaths? This makes absolutely no sense whatsoever.

And remember that in the Africa report, which the UN currently calls its “most extensive study yet,” the UN acknowledged that the causes of radicalisation “are multiple, complex and context specific” and “defy easy analysis.”

This thoroughly refutes the manifest ease with which the UN proclaims, without cause, that so-called conspiracy theories “fuel violence and violent extremist ideologies.” This begs the question: what on Earth does the UN think “violent extremism” is, if not terrorism?

The bottom line is that, by its own admission, the UN has absolutely no evidence to support any of its “conspiracy theory” assertions. Rather, the UN is simply making up its entire “conspiracism” thesis from whole cloth.

In reality, so-called “conspiracy theorists” are overwhelmingly ordinary people with legitimate opinions that span a wide range of issues. Their opinions do not lead them to adopt extremist ideologies or to commit violent acts. There is no evidence at all to support this widely promulgated contention.

Nor are alleged “conspiracy theorists” a unique group of malcontents with psychological problems. The only defining characteristic these people possess is that they exercise their right to question power.

They do not seek to undermine democracy but, rather, exercise the rights and freedoms that democracy is supposedly based upon. It is this behaviour that the State deems unacceptable and that leads the State and its “epistemic authorities,” including the legacy media, to label them “conspiracy theorists.”

This observation in no way implies that the conspiracy theorists are always right. Conspiracy theories can be bigoted. They can be ridiculous. They may lack supporting evidence. They may cause offence. And they are sometimes just plain wrong. In other words they are just like any other opinion. But, equally, there is nothing inherently inaccurate or dangerous about every opinion labelled “conspiracy theory.”

There is only one way to ascertain if an alleged conspiracy theory is valid or not: examine the evidence. Unfortunately, the conspiracy theory label was created specifically to discourage people from looking at the evidence.

There are countless examples of the conspiracy theory or theorist label being used to hide evidence, obscure facts and deny legitimate concerns. In Part 2, we will look at a few of these examples and explore the wider geopolitical context in which the conspiracy theory label is deployed.

Thank you for writing this. It’s urgently needed and well executed. I’m chomping at the bit for Part 2.

Conspiracy theories arise from government secrecy and lack of transparency on the one hand, and observable corruption on the other. But rather than change their highly profitable nefarious ways, the ruling class has found it easier to discredit their detractors, especially since they have the mainstream media-sphere at their beck-and-call.

Thanks Charles. Yep, that is a good summation.

I am looking forward to the rest of the series. I agree fully with the article the term conspiracy theorist has been weaponized to silence people and imply any beliefs you hold are crackpot beliefs divorced from reality. It would be useful to have a list of conspiracy theories which have come true. Obviously if conspiracy theories come true this proves conspiracy theories are not absurd ideas based on fantasy.

Good idea. Thanks.

Iain, this article criticises others’ knee-jerk response but reads as a knee-jerk response itself, seeming shallow and blinkered. And, much of it reiterates bits of previous articles of yours.

Addressing labels in general sees deeper and further calmly, countering bait: –

Labels per se are inaccurate because no two individuals are exactly the same, each being unique and, labels are too narrow for the whole of even one person.

As inaccurate info inevitably muddles, labels are best ignored. Otherwise any response, whether rejection or acceptance, goes into a group controlled by label instead of by own independent decisions.

And, groups, being totalitarian, eradicate the individual.

Thus, irrespective of whether label is supposed to be derogatory or complimentary, unless it’s ignored, self-control is lost, scuppering own self-esteem.

The basic biological fact of life that each individual, including self, is unique means categories are rubbish and inherently detrimental to all.

Why not more self-confidence instead of using labels as props? Given that labels are so inaccurate they’re rubbish, is any label worth the value of own attention, or beneath it?

Unless you ignore labels, you trap self in a load of rubbish. None travel far or fast with that baggage.

Labelling anyone else necessitates first labelling self for comparison. Thereby limiting own freedom by complying with chosen label but, then blaming and attacking others for that self-inflicted trap.

It’s less hassle to deal with each individual as is. Thus learning more accurate information simply by respecting each as a unique individual, fallibility and all i.e. functioning on facts instead of on the hearsay of labels.

Summary: Labels cause hatred and ignorance, thereby crippling love and peace.

Now do you see why “shallow and blinkered”?

Thanks Jane. Yes it does recover some points I’ve made elsewhere and adds some new research. The reason why I’ve done this will become more apparent in Part 2. But essentially it was important to me to bring together my rebuttal of the following canards in one piece:

While I appreciate your point that discussing the label potentially lends it credence, I do not believe this is a label we can afford to ignore. As will become more evident in part two, it is a propaganda construct upon which legislation is based and which forms the core of some very draconian censorship at the global governance level.

I do not agree that this is in any way a self inflicted trap. If we ignore the label it will still be used against us and the rest of the general population. Therefore, I maintain that it is important to address the propaganda label.

Hi Iain, we’ve been through ‘categorisation’ issue before and it seems we’ll never manage to agree about it, so might as well agree that’s way it is on that one.

Many thanks for publishing my comment. I think that while generic alone works for some, an illustration as well is needed by others, which you are providing.

My concern was absence of warning about all labels. Whether ancient or new, all labels are detrimental, often literally lethal e.g. prejudices, recently broken families.

‘Group of people who supposedly can be identified as’ is as I said for all labels.

I think paying attention to labels pays over the odds by under-valuing self: nothing sells unless bought and, reject or accept both buy into tribal warfare.

Refraining from buying empowers self but buying disempowers self, empowering labeller instead: self-restraint keeps own strings, buying hands them to labeller.

The more they stand to benefit, the more pressure they apply and the more to our detriment if we hand self over to them.

Flat refusal to shift either way, dug-in heels, ‘passive resistance’, obstinately going own way: it’s my birth-right to my own strings I’m intent on keeping.

Maybe my word ‘ignore’ lacked clarity:

‘global governance’ fails unless we connect. Messages unreceived are impotent: no TV or internet connection, no panic in 2020. Rejection and acceptance actively connect to label, flat refusal to shift either way (ignore) doesn’t but is more effort.

If problem with propaganda is it’s manipulative, so too are all labels and adverts; actively refusing to buy what’s advertised is no less manipulated than buying.

Why fear legislation? It’s only own choice that stops us breaking rules. If majority choose to break them, rules collapse. Legislation only stands if majority comply.

If a majority do comply, it’s their choice and we should take that into consideration irrespective of whether or not it’s same as own.

The thing that annoys me most about the phrase Conspiracy Theory is the way it flatters the vanity of the person using it into thinking he has a deep and sagacious understanding of how the world works. ‘Oh no, no, no, they could never keep it secret.’

Me: Face+palm

Thanks Malcolm. I would add what they consider a secret is really just an event or narrative that hasn’t been reported or “officially acknowledged” by the “epistemic authorities.” Conspiracy theory is often defined as a belief in “secret” plots. But, of course, if they were genuinely secret no one could possibly know anything about them. I have argued strongly that people called conspiracy theorists are actually pointing toward real evidence that reveals the alleged secret, rendering it a secret no longer. It only remains a “secret” in the eyes of the epistemic authorities and those who only accept reality if it is confirmed for them by the epistemic authorities.

My family know me as a conspiracy theorist because I do not swallow wholesale things that are said by the state. When events occur that justify detailed forensic investigation yet no such investigation takes place or, if it does, important evidence is withheld for reasons of national security, I question the narrative. The media does a disservice by not behaving in a similar way

Absolutely Reginald. The legacy media should hold power to account but it rarely, if ever does. I suspect this is why increasing numbers are turning toward the independent media. But the state always seeks to control the flow of information, hence the censorship of the independent media and protection for the legacy media.

This is a fabulous piece Iain. Thank you.

Hi Iain

You used the term “inconvenient evidence” and I wonder if that is a phrase which could be used for all or most challenges to the status quo?

Do you think it would be hard for the mainstream to abuse the term?

A quick search suggested the following;

Inconvenient: causing trouble, difficulties, or discomfort

Evidence: the available body of facts or information indicating whether a belief or proposition is true or valid

All the best

Thanks Steve, I think it is a useful term and one already covered by so called “malinformation” which the UN defines as: – Information that is based on real facts but is manipulated to inflict harm on a person, organization or country.

https://iaindavis.com/UKC/UN-ismMapping.pdf

That is malinformation is demonstrably true and evidence based, but inconvenient.

Yes Iain, people are indeed turning towards the independent media, but witness the coordinated attacks currently being undertaken against various outlets & individuals that don’t toe the line & stick to the parroted narrative.

…And all this before the ink has set on the Online “Won’t somebody Think About The Children” Safety Bill.

Watch that one grow arms & legs.

Indeed Mike. I think people are wrong to think the Online Safety Act will be constrained to social media. It will extend across the internet. ISP’s and individual blogs such as this one will not only have their reach removed but will eventually be “taken down” from the internet completely in my estimation.

This quote attributed to Casey pretty much sums up anything to do with the concept of conspiracy theories. The term was coined by the CIA in the 1950s. Dulles Operation Gladio it’s not hard to connect the dots.

We’ll know our disinformation program is complete when everything the American public believes is false.”

William Casey, former director of the CIA, upon being asked what the goal of the agency was (in 1981).

Thanks Mark. Yes, it is a telling quote.

The American political science professor and author of Conspiracy Theory in America Lance DeHaven Smith thought that most of the conspiracy theory issue could be changed if we labeled the ones about government differently.

He thought they should be called SCAD State Crimes agajnst Democracy.

It would certainly legitimize real discussion around the issues.

Thanks Jan. I haven’t read the book in full, only excerpts. Must read it completely. Yes that is a very useful suggestion. Just downloaded it so will do.

Democracy is the wrong term to use…a “democracy” is mob rule, period, full stop

State Crimes Against the Constitution is better, SCATC, IMHO

Praise the Lord and Pass the Ammunition!

“Representative democracy” is certainly mob rule. “Democracy” is rule by trial by jury and is something else entirely: – https://iaindavis.com/long-live-democracy/

Interesante tu artículo.

Teórico de la conspiración apunta a desacreditar el hecho en sí (incongruencias de la versión oficial del 911, Oswald, Apolo, etc), pero más aún a la persona que las postula o defiende (lunático o peor).

Eso impide el diálogo.

“No analices el 911 con él, pues es un lunático”.

Tendemos a dividirnos en blancos vs negros, demócratas vs republicanos, equipo A vs equipo B, y así.

Con lo que has estudiado, sería bueno acuñar o encontrar un término opuesto sencillo y masificable, que lo contrarreste y prestigie, para poder avanzar en esta batalla dialéctica.

Por ejemplo, es un “verificador” (o un “especialista”) de la conspiración.

O un “validador de fallos” históricos.

O etiquetar como “creyente oficial”, al que usa peyorativamente el término “teórico de la conspiración”.

Thanks Diego. – translation:

Your article is interesting. Conspiracy theorist aims to discredit the event itself (inconsistencies of the official version of 911, Oswald, Apollo, etc.), but even more so the person who postulates or defends them (lunatic or worse). That prevents dialogue. “Don’t discuss 911 with him, he’s a lunatic.” We tend to divide ourselves into whites vs. blacks, Democrats vs. Republicans, A-team vs. B-team, and so on. With what you have studied, it would be good to coin or find a simple and massifiable opposite term, which counteracts and gives prestige to it, in order to advance in this dialectical battle. For example, he is a “fact-checker” (or a “specialist”) of the conspiracy. Or a historical “fault validator.” Or label as an “official believer,” the one who pejoratively uses the term “conspiracy theorist.”